Ridley

Scott’s TV documentary series Prophets

Of Science Fiction (2011-2) starts with Mary Shelley and shows how medical science has advanced since her era.

Mary Shelley was haunted by spectres of death and yet such progressive

morbidity fed into her classic novel, a book arguably best made into a movie as

Kenneth Branagh’s epic Frankenstein

(1994). Shelley’s impact on morality and SF literature, and global culture in

general, is explained by scientists (such as Michio Kaku), genre authors

(including Kim Stanley Robinson), and Shelley biographers who provide meaty

insights linked by presenter Scott’s own philosophical musings. With its

frequent use of dramatic reconstructions, plus animated visuals with narration,

this recalls classic TV programmes like Carl Sagan’s Cosmos (1980). Many authoritative interview clips ensure that a

variety of viewpoints are presented, alongside promotional material from today’s

innovators.

Second episode H.G. Wells charts

wholesale creativity with iconic titles including The War Of The Worlds (filmed 1953, remade 2005), and The Time Machine (filmed in 1960, and

curiously remade, by Simon Wells, in 2002). There’s also The Invisible Man, and The

Island Of Dr Moreau, with details here showing how new tech follows the

notions lifted from Wells’ work. Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven and American author

David Brin are most notable as commentators. The truly prophetic imagery for

Wells’ movie Things To Come (1936)

gave dramatic optimism to social criticism but Wells’ predictive legacy is

often ignored when politics meddles with possibilities of scientific progress. Time

for a pause... during this TV show’s six episodes, I re-watched Wells’ Time Machine remake, and found it quite

reasonably entertaining with enough quality special effects and generic

tensions to reverse my previous thinking that, at best, it was mediocre sci-fi

or wholly derivative escapism partly inspired by some bleak Darwinian

futurism.

Stanley Kubrick’s co-creator of supreme movie 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), author Arthur C. Clarke, obviously deserves his own episode here, and this

chapter brings together his practical invention of telecom satellites and

theoretical space elevators in his book The

Fountains Of Paradise (1979). Another of Clarke’s co-writers, Gentry Lee, offers

enthusiastic insider commentary. Few other SF writers can possibly match Clarke’s

importance to modern literary and media fields of genre speculation. And so

this potted biography and focus on the maturation of hard-SF themes throughout

the 1960s and 1970s. After this episode, I re-watched Christopher Nolan’s

Interstellar (2014), deciding to try harder to like it more this time. And so I

did, because it makes better sense today, especially for its glowing optimism, that ends (well, sort

of..?) where Clarke’s hugely under-rated book, 3001: The Final Odyssey (1997) starts, with a cleverly witty

tribute to pulp sci-fi’s own time-warped hero, Buck Rogers.

George Lucas seems

a decidedly odd choice for this TV series, but his creation of sci-fi adventure

franchise Star Wars (1977), exploded

SF from cult novels and niche cinema, into mainstream popularity. His genius

was to make intellectual imagination into big-screen fun. Amusingly, this

episode mostly explores how cutting-edge tech is inspired by hardware in Star Wars media - as if Lucas was the

first to imagine cyborgs, robots, levitation, and mental super-powers; despite

acknowledging its exactly what everyone wants for Xmas.

For a genre timeline accuracy, Jules Verne should really have been

the subject of this TV series’ second episode, but as its fifth this does gain

a fittingly ‘retro’ feel, and slippage from optimistic adventure novels to

gloomy themes in its study of Verne’s later dark works of dystopian worlds.

Literary scholar George Slusser and comics writer Matt Fraction provide interesting

comments. Verne’s best loved, and perhaps most influential’ novel 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1870) was

adapted several times for the screen, and its versions include these four...

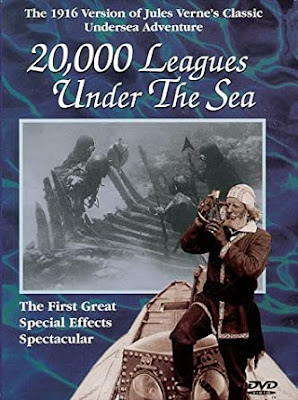

Stuart Paton’s epic silent movie 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1916) is the first submarine

spectacular, partly using Verne’s sequel novel The Mysterious Island (1874) as its source material. This is a tale

about maritime disasters, pirates, shipwrecks, and castaways, with underwater

photography, and some rather eerie scenes of divers hunting sharks on the

seabed. Rendered in full scale, the super-sub Nautilus is wholly convincing but

Captain Nemo, a former prince of India, is costumed rather like Santa Claus

with a bandana.

With big

advantages of sound and colour, Disney’s engagingly cinematic 1954 production

has escapades to spare, with Kirk Douglas as harpooner Ned Land facing down

James Mason’s memorable Nemo aboard his Nautilus - here an engineering

masterpiece of steam-punk designs, three decades before the cyberpunk movement

was itself quite fashionable enough for easy recognition as a distinctive

sub-genre. A giant squid provides the monster action. Although brooding Nemo’s

organ-music suits the movie’s darker theme of vengeance, I always felt that

director Richard Fleischer’s ocean adventure would have worked far better

without its awful songs.

Hallmark’s

TV movie, briskly directed by Michael Anderson, stars Richard Crenna as

Aronnax, Ben Cross as stern Nemo, and Paul Gross (from TV cop show Due South) as Ned. Whereas Disney’s

adaptation lacked a strong female lead, this version casts Julie Cox as

professor’s daughter Sophie, a scientist in her own right, when she’s not an

obvious romantic interest for class conflict and cultural rivals Ned and Nemo.

Sleek, powerful, and modernist, but with stylish interiors, set designs for

this Nautilus compare well to Disney’s with better special effects in some

sequences, except for the computer animation of a deep-sea monster that only

works as surrealism of dragon-slaying, not convincing sci-fi.

Also released in 1997, director Rod Hardy’s two-part TV serial

benefits from casting of Bryan Brown as Ned Land, but its real star is Michael

Caine as Captain Nemo, while Mia Sara plays his daughter Mara. When a warship

hunts a mysterious behemoth, the young heroes are lost at sea. Soon

taken as POWs aboard the Nautilus, French marine biologist Arronax (Patrick Dempsey),

with Ned, and black companion Cabe (Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje), explore the

baroque submarine, before they join a sea- hunting party. They manage to adjust

to captivity, without hope of escape, especially from cut-priced undercooked

visual effects of seabed volcanoes. An ordeal of survival, trapped beneath

Arctic ice, develops a new solidarity with Nemo’s agenda, despite legal,

ethical, and moral, differences. Verne is written into this narrative as a

famous author inspired by others’ adventures. Arronax is haunted by nightmares

of drowning, and contends with losing a hand, but Dempsey makes for a rather

bland hero, whether in pursuit of knowledge, or freedom.

Also inspired by Verne, British movie Captain Nemo And The Underwater City (1969) begins with a

disaster when passengers from a sinking ship are rescued by frogmen from the

Nautilus. Senator Fraser (Chuck Connors) meets Nemo (Robert Ryan) who takes

them to safety in the domed city Templemer. James Hill directs this family

adventure with an eye for spectacle, including golden sets, and a scuba-diving

tour with shark-attack action, but there is rather too much slapstick from

comic-relief characters. A Theremin recital adds to other-worldly charms. One

meddling escapee risks destruction but only the saboteur dies. Oceanic drama

continues when a giant mutant manta-ray menaces the Nautilus. Ryan’s

grandfatherly Nemo breaks clear from Verne’s traditional dark genius, but it’s

quite expected in this colourful fantastique, with Nanette Newman as a

Victorian single-mother bringing up her only son to respect peaceful authority,

as she considers the possibilities of staying to live in a utopian realm.

The Amazing Captain Nemo (aka: The Return Of Captain Nemo, 1978),

updates Verne for a present-day TV revival when US navy divers find the sunken

Nautilus to awaken greybeard Nemo (Jose Ferrer), soon recruited to combat the

super-terrorist (Burgess Meredith), blackmailing America for a billion bullion

ransom in a world where Verne’s biography of Nemo was clearly mistaken for

fiction. Only three episodes of this failed series were made, and later edited

into this 102-minute movie, now released onto DVD, from Warner’s archive. After

he saves Washington, DC. from a doomsday rocket, superhero Nemo accepts another

mission for atomic-powered Nautilus, but with nuclear advisor Kate (Lynda

Day George), and a saboteur (Mel Ferrer, no relation to Jose), aboard. In their

final adventure, Nemo discovers lost Atlantis.

Alan Moore’s millennial graphic novel and following comic-book

series The League of Extraordinary

Gentlemen was adapted for sci-fi cinema as Stephen Norrington’s blockbuster

LXG (2003), about steampunk

superheroes assembled to save the British Empire and stop WW1. The team

includes Allan Quatermain, an invisible man, vampire Mina Harker, immortal

Dorian Gray, and Indian pirate Captain Nemo. His ‘Sword of the Ocean’, Nautilus,

gets the heroes across the English Channel to Paris, to recruit hulking brute

Mr Hyde, and then Nemo’s super-submarine sails into Venice, continuing its

mission, despite being damaged by enemy bombs, all the way to a finale in

Mongolia.

Ex-military and politically-minded, Robert Heinlein wrote SF that, intentional or not, courted

controversy, particularly with books like Starship

Troopers (1959), winningly filmed by Paul Verhoeven in 1997. But then Heinlein

created Stranger In A Strange Land,

to become a play-book for hippies in counter-culture America. So, whereas

previous big-time SF authors covered in this TV series actually formed the

nascent genre, Heinlein helped to shape basic tropes into explosive or

exploitative new material of competent heroes. Stories in an existing

frame-work of ideas, like The Moon Is A

Harsh Mistress (1966), about the rebellion of a Lunar colony, prompt

discussion about humans in space. Harlan Ellison appears, yet only briefly.

A cult writer whose fiction created an extraordinary density of

intellectual meanings and emotional interpretation, Philip K. Dick was influenced by his own paranoia and use of drugs.

And so his predictive novels and idea-driven short-stories would be readily

adapted to modern cinema where virtual reality, alternative worlds, and

unreliability of memory form intriguing narratives of Orwellian surveillance

and precognition that undermine lifestyles and fracture societies. Mankind

crumbles into its own imaginary plots, sinister culture, and questions of truth

between science and human experience. This episode is probably the most

fascinating in the whole series, and ends when Ridley Scott ponders: “Aren’t

most prophets troubled souls?”

Isaac Asimov

formalised robot stories with a new complexity of relationships between machines

and their human creators, as far more sophisticated than rampaging monsters in

pulp-SF. His work suggests that progress from industrial robots - used on

assembly lines in factories, to developing advanced tools - for spinal and

cranial surgery, is totally inevitable. Later, Asimov became the world’s

greatest SF author of non-fiction about science.